Thoughts on Oscar Niemeyer

For weeks now, I have been checking the news daily, afraid that I might somehow miss the news that architect Oscar Niemeyer had died.

When he did die, I found out almost immediately. Initially, I was sad, but the more I thought about Niemeyer, the more I felt that he was not simply my favorite architect; his architecture changed the way I see things.

I am not a worshipper of Niemeyer. He could be cantankerous, crotchety, and absurd. His tantrum a few years ago over the city of São Paulo not tearing down part of the marquee at Ibirapuera Park (altering the original plan) when they built the auditorium fell somewhere between infantile and beyond the pale.

Yet, I did have an extraordinarily affectionate relationship with his architecture. I started taking pictures of it a decade ago; at that time, I mostly took pictures of architecture and architectural elements. Niemeyer inspired me to look beyond the interesting and find the sublime. His exterior lines were monumental; the interior curves and shadows, elegant.

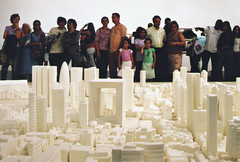

Some of his sites, like the Memorial da América Latina and even Brasília, became places that seemed surreal when they were empty (which was most of the time) post-apocalyptic when filled with crowds that seemed to be confined into a dream landscape in the middle of nowhere.

Others, like the MAC Niterói, the Museu do Olho, and the Brasília Cathedral, were simply breathtaking.

When I started taking pictures of Niemeyer’s architecture, I was trying to translate the emotion that welled up inside me when I saw or entered his buildings. Indeed, the curves, shadows, juxtapositions, and lines evoked strong emotions in me that I could not possibly express in words and struggled to portray in photographs. Luckily, Cristiano Mascaro was a more successful photographer of Niemeyer’s architecture, often finding angles and details that the architect himself may not have imagined.

From Niemeyer’s work, I learned to look again at buildings that I had not previously found beautiful. I came to see the International School and Modernism as well as contemporary or subsequent movements in new lights. Some of these buildings (and to some eyes, Niemeyer’s as well) were ugly. I started to love the ugly. I started to seek it out. I essentially stopped taking pictures of architecture in general and Niemeyer’s buildings in particular.

I still visit them and commune with them. I never see or step foot inside of a Niemeyer building without thinking about the architecture. Sometimes, I still see lines or details in Niemeyer’s buildings that make me weak in the knees. I still feel passion for a particular tree that draws shadows on the Oca building. Yet, I guess I realized that the beauty of Niemeyer’s architecture is self-evident; it doesn’t need my help and I don’t need to record it on film to remember what I saw. Less apparent is the simple elegance of yellow leaves and an abandoned building in Troy or a pile of concrete bricks in São Paulo. Those are the things that I want to share about my world—things that others might not see, and certainly wouldn’t find beautiful.

Of another architect, Paul Simon wrote, “Architects may come and/Architects may go and/Never change your point of view.” Every once in awhile, however, one comes along and turns your perspective on its head.

Yet, I did have an extraordinarily affectionate relationship with his architecture. I started taking pictures of it a decade ago; at that time, I mostly took pictures of architecture and architectural elements. Niemeyer inspired me to look beyond the interesting and find the sublime. His exterior lines were monumental; the interior curves and shadows, elegant.

Some of his sites, like the Memorial da América Latina and even Brasília, became places that seemed surreal when they were empty (which was most of the time) post-apocalyptic when filled with crowds that seemed to be confined into a dream landscape in the middle of nowhere.

Others, like the MAC Niterói, the Museu do Olho, and the Brasília Cathedral, were simply breathtaking.

When I started taking pictures of Niemeyer’s architecture, I was trying to translate the emotion that welled up inside me when I saw or entered his buildings. Indeed, the curves, shadows, juxtapositions, and lines evoked strong emotions in me that I could not possibly express in words and struggled to portray in photographs. Luckily, Cristiano Mascaro was a more successful photographer of Niemeyer’s architecture, often finding angles and details that the architect himself may not have imagined.

From Niemeyer’s work, I learned to look again at buildings that I had not previously found beautiful. I came to see the International School and Modernism as well as contemporary or subsequent movements in new lights. Some of these buildings (and to some eyes, Niemeyer’s as well) were ugly. I started to love the ugly. I started to seek it out. I essentially stopped taking pictures of architecture in general and Niemeyer’s buildings in particular.

I still visit them and commune with them. I never see or step foot inside of a Niemeyer building without thinking about the architecture. Sometimes, I still see lines or details in Niemeyer’s buildings that make me weak in the knees. I still feel passion for a particular tree that draws shadows on the Oca building. Yet, I guess I realized that the beauty of Niemeyer’s architecture is self-evident; it doesn’t need my help and I don’t need to record it on film to remember what I saw. Less apparent is the simple elegance of yellow leaves and an abandoned building in Troy or a pile of concrete bricks in São Paulo. Those are the things that I want to share about my world—things that others might not see, and certainly wouldn’t find beautiful.

Of another architect, Paul Simon wrote, “Architects may come and/Architects may go and/Never change your point of view.” Every once in awhile, however, one comes along and turns your perspective on its head.

Labels: Oscar Niemeyer, photography